Barely Scratching the U.S. Budget Challenge

Setting the New Debt Ceiling Deal in Context

The debt ceiling agreement made by President Biden and Speaker McCarthy over the Memorial Day weekend has now been passed by the House as the Fiscal Responsibility Act. One assumes it will soon pass in the Senate, given Democrat’s control of that chamber. That’s all great because it’s a big step away from an unprecedented default on our government debt.

The GOP justified threatening to default and thereby likely sending the country into a recession as necessary for curbing the rapidly rising national debt. So, the big question is was anything accomplished?

NBC News reports that Speaker Kevin McCarthy said:

The deal was "historic," as it would amount to "cutting spending year-over-year for the first time in over a decade."

Let’s take a look at it.

The Big Picture

Rather than just listing the elements of the bill like everyone else, let’s understand it in context. As shown in this handy chart from USAFacts, the problem is that we are overspending the country’s revenues.

The graph depicts the deficit as somewhere in the neighborhood of $1 trillion dollars. If you want a deep dive into it, the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Deficit Tracker goes into detail on a month-by-month basis.

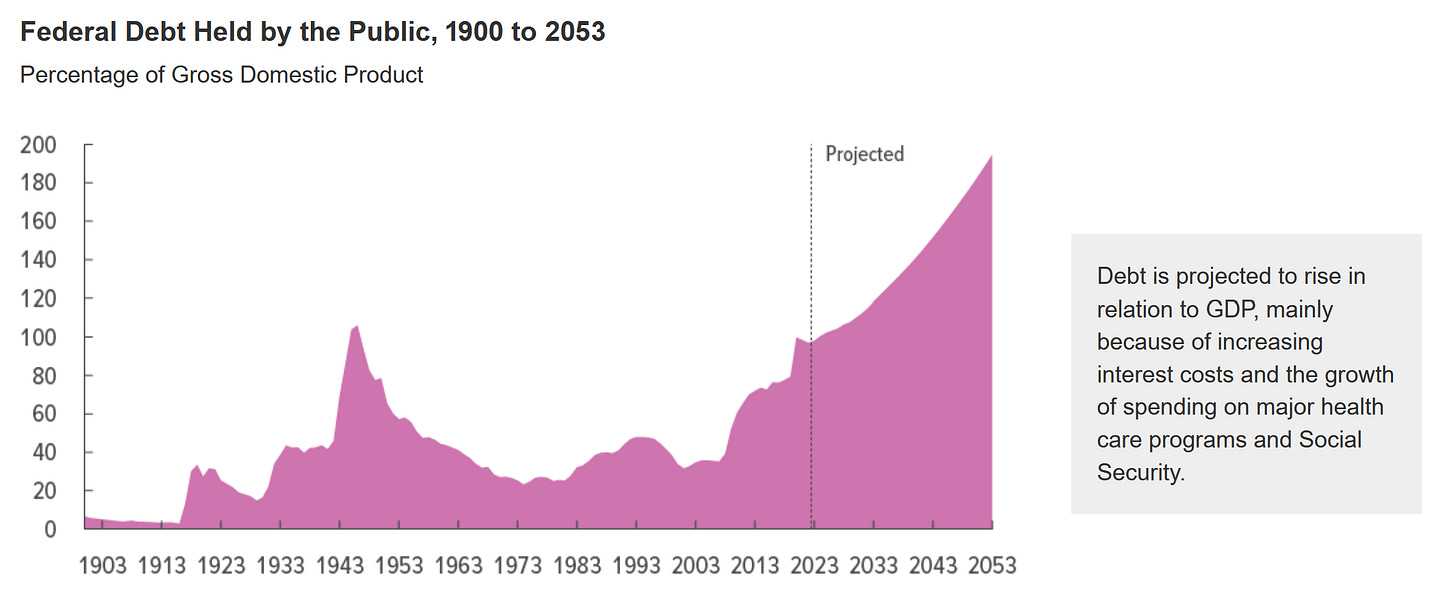

That size of shortfall adds to the total debt pretty quickly, as shown below in this graphic, also from USAFacts.

So, while recent data seems to suggest that spending and revenues are converging, they aren’t projected to converge enough. The national debt is already quite high, so we need to not only be on a budget but pay it down. In fact, The Congressional Budget Office projects a continued, rather dramatic, increase.

We can go into the root causes another time, but you can see from the note on the right side that the primary drivers are spending on:

Health care

Social security

Interest

None of these are addressed by the debt ceiling deal, and all of these items—due to the aging of the population and the nature of interest rates—are increasing. We have little control over their natural rise.

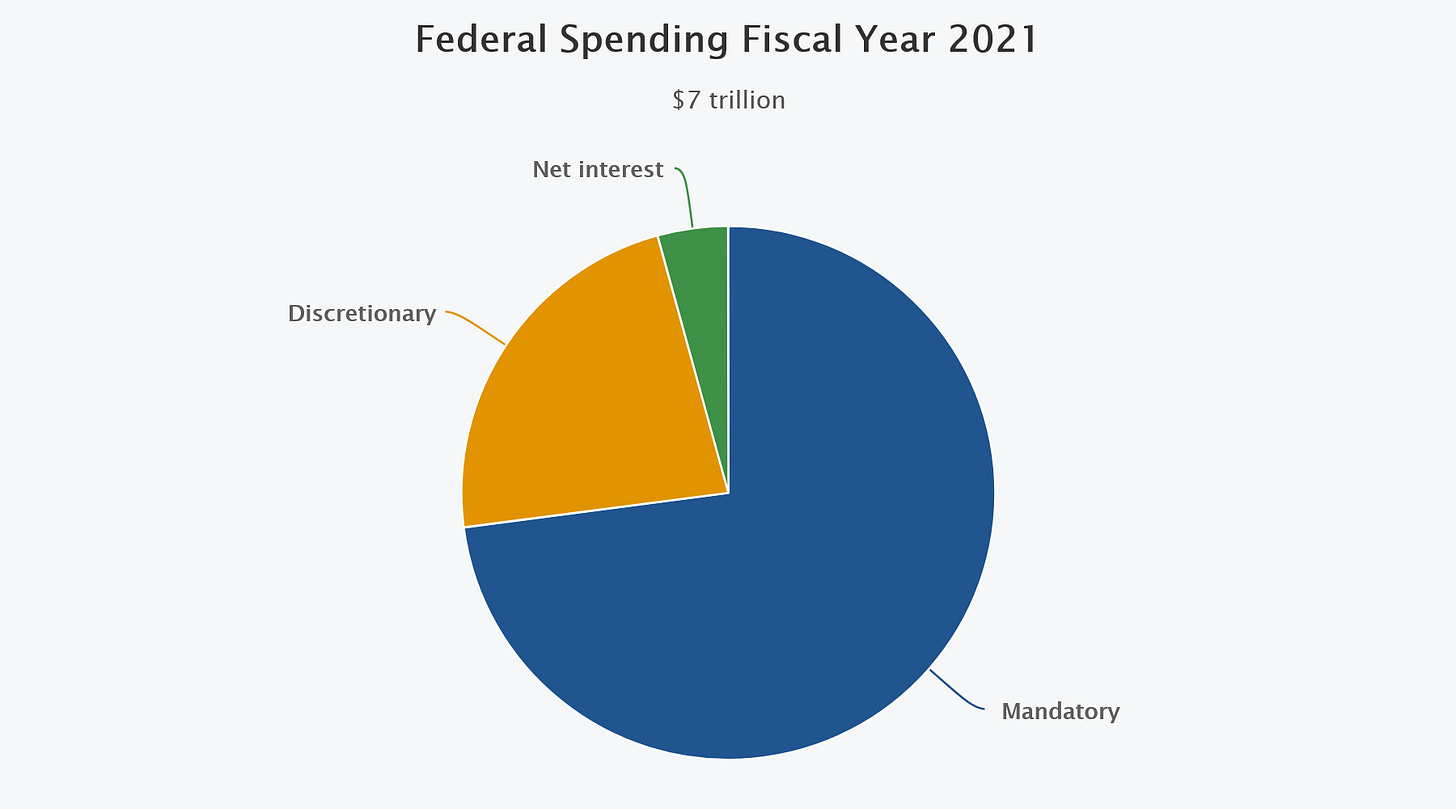

To understand this better, we can rely on this wonderful site, the National Priorities Project. Their graphs depict the problem well, so I’ll show them even though they are from FY2021. That’s close enough for now. You can visit the site for a deeper explanation.

To set the context for understanding where the effects of the debt ceiling deal occur, first note that the U.S. Government has three main categories: interest on the debt, mandatory spending, and discretionary spending.

As you can see, mandatory spending and interest payments are most of it, leaving a little less than 25% for discretionary spending.

Effects on Mandatory Spending

Mandatory spending is determined through legislative action by Congress. The breakdown is shown in the graph below, which includes Social Security and Healthcare, which are two of the big drivers of the debt increase.

Note that the debt ceiling deal does not address either interest payments or any of these mandatory categories directly.

Effects on Discretionary Spending

The debt ceiling bill mainly affects discretionary spending—by putting limits on what can be agreed on in the upcoming appropriations process, which determines discretionary spending.

The major areas of discretionary spending are shown below.

As you can see, defense (Military) spending is by far the biggest part. The debt ceiling bill keeps defense spending flat at $886B for FY2024 but allows it to rise to $895B in FY2025.

Non-defense categories are kept almost flat at the FY2023 level. There is some negligible recapture of COVID-19 relief funds and money to fund the IRS. This doesn’t make a big difference, as NBC News reports:

Factoring in adjustments, the White House projects that when veterans funding is set aside, nondefense spending would barely change — with a slight reduction overall from 2023 to 2024.

"It's flat. It's a difference of about $1 billion," a White House official said.

That’s $1B against a $1000B shortfall, in case you lost count.

Wrapping It Up

Pretty clearly, the debt ceiling bill does little to change the fundamental issue of government overspending and rising national debt. It does keep discretionary spending—a minor contributor to the overall problem—relatively flat by feeding some constraints into the appropriations process about how much spending can increase, which is where budget discussions should be occurring anyway.

I’m for controlling spending. It seems like the right thing to do for the long term. But, I’m not sure this debt ceiling debate and the resulting deal did anything for that. It was probably mostly for show as I argued previously.

What surprised me though was that it appears to have gone fairly smoothly and quickly so far. Like many people, I was expecting a lot of haggling, re-voting, and a final decision at 11:59 pm on June 5. Let’s hope all stays smooth.

Possibly, this is where Biden’s quiet magic and experience with Congress came in, although I think that, rather than argue about who “won,” we should appreciate both Speaker McCarthy and President Biden for working together in a tough environment.