The "NATO Provoked Us" Fallacy Exposed

Putin is the biggest force for strengthening and expanding NATO

Ukraine’s request to join NATO is a key topic for the NATO 2032 Vilnius Summit. While Ukraine definitely won’t be admitted yet, vigorous meetings have already been held to align on what assurances to offer the embattled former Soviet Republic.

Russia has warned repeatedly that admitting Ukraine to NATO would threaten Russian security. This alleged threat was central to Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine. As the AP News reports,

Putin long has described NATO’s expansion to Russia’s borders as the top security threat to his country. When he sent troops into Ukraine on Feb. 24, he cited increasingly close military ties between Kyiv and the West as a key reason behind his action.

While on the surface this seems understandable, and many people agree, including some Western pundits, the claim is less defensible when you look deeper into it.

The Basic Premise

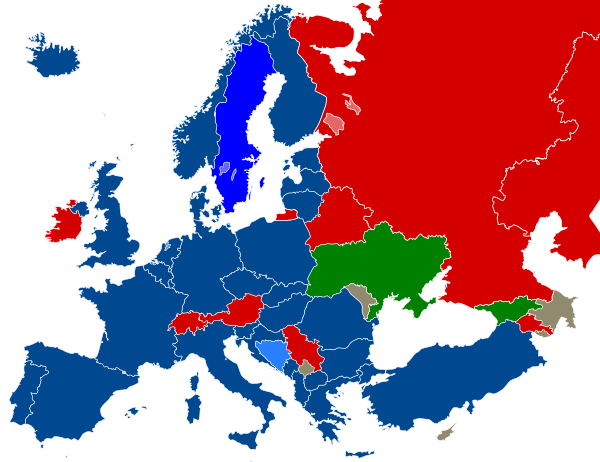

The fundamental plank of this “NATO provoked me” argument is that NATO has significantly expanded over the years. Of course, this is true: Since the fall of the Soviet Union up to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many of the former Warsaw Pact countries did join NATO. The expansion is clearly shown in this diagram from the BBC.

When looking at the diagram, one does kind of feel like “Ok, he’s being surrounded by the enemy,” so maybe there is something to this provoked thing.

NATO’s Intentions

Any conclusion about NATO threatening Russia would have to come from drawing conclusions from the map and “reading between the lines.” Officially, NATO has always maintained that they were a defensive organization and has never stated an intention to threaten Russia.

In fact, initially after The Cold War, NATO sought to transition to a peacekeeping organization. As an article from The Hill explains.

NATO’s enlargement began in the mid-1990s, at a time when the alliance was embarking on a strategic shift, focusing on out-of-area operations instead of territorial defense. NATO urged new member states to focus on specific cutting-edge expertise, and programs for partner countries like Georgia were mostly about training for peacekeeping operations in places like Afghanistan. NATO’s shift is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that the alliance lacked a workable plan to defend the Baltic states when Russia invaded Georgia in 2008.

At that time, in May 1997, NATO and Russia concluded the Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation, and Security, which set up a permanent body for consultation and coordination and was intended to lay the basis for a cooperative relationship with Russia.

Among other things, the Founding Act reiterated that NATO had “no intention, no plan and no reason” to place nuclear weapons on the territory of new member states. The Act also noted that NATO saw no need for the “permanent stationing of substantial combat forces” on the territory of new members. These statements reflected the Alliance’s effort to make enlargement for Moscow as non-threatening as possible in military terms.

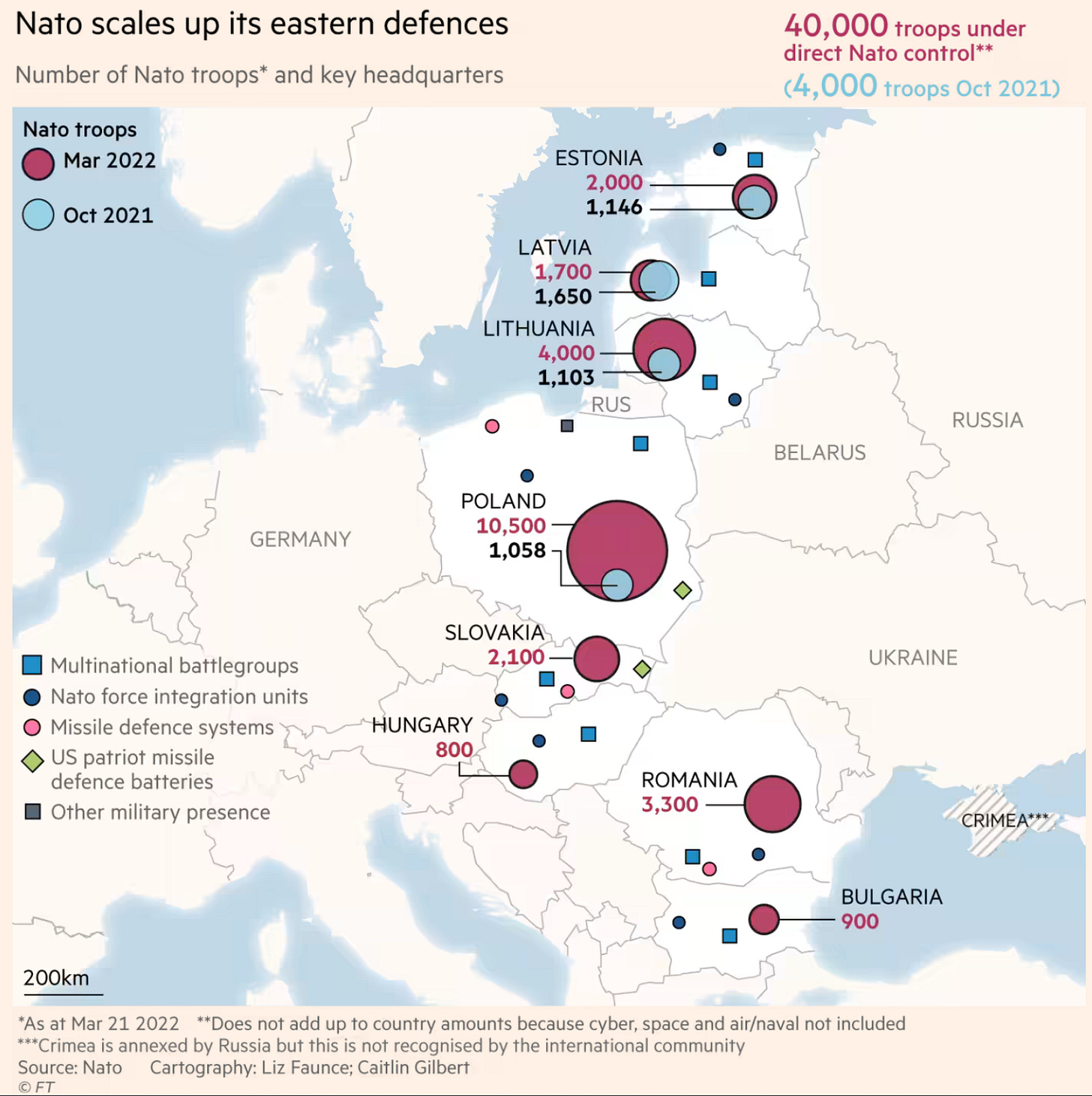

Consequently, before the Russian invasion of Crimea, NATO deployed virtually no combat forces on the territory of its new members. Even then, NATO only deployed, on a rotating basis, multinational battlegroups numbering 1,000-1,600 troops in each of the three Baltic states and Poland. These were described as “no more than tripwire forces.”

As tensions rose in 2021, these forces increased to roughly 4,000 troops. Then, according to the Financial Times, after the Russian invasion in February 2022, NATO forces increased to 40,000 troops. This was in contrast to an estimated Russian strength of 200,000 troops, thousands of tanks, and hundreds of aircraft pouring into Ukraine.

Of course, the Eastern NATO countries had their own standing armies as well. These are roughly shown below.

Poland: 196,000 active troops, 110,000 reserves

Romania: 76,000 active troops, 56,000 reserves

Bulgaria: 36,000 active troops, 20,000 reserves

Hungary: 25,000 active troops, 22,000 reserves

Slovakia: 19,000 active troops, 15,000 reserves

Czech Republic: 20,000 active troops, 10,000 reserves

Nonetheless, there was no positioning of forces to invade Russia. Russia has argued that missile systems could be installed and hit Moscow. However, the reality is that these existing missile batteries were only a few primarily defensive systems, such as Patriot systems, also shown on the diagram.

The Promise That Wasn’t

Some supporters of the “Russia was provoked” argument claim that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was assured that NATO would not expand. However, there was no such guarantee.

From The Hill,

Even the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, has denied that the issue of NATO enlargement was even discussed at the time. Russian President Vladimir Putin himself did not have much to say about NATO enlargement until his infamous speech at the 2007 Munich Security Conference.

At any rate, it was never put in writing. So even if some assurances were discussed, it doesn’t matter. It makes no sense to hold governments accountable for some statements allegedly made by long-gone government officials during some meetings 40 years ago that were never captured in signed documents.

What did make into multiple signed agreements over that time period were commitments by Russia not to violate Ukraine’s sovereignty.

Provoking Is Not Illegal

Another argument often given to support Russia is the “U.S. wouldn’t tolerate it” argument. For example, what if China established a military base in Mexico?

David Lane, writing for the World Economics Association, claims there is a “norm” among nations that they can do illegal things when their security is threatened.

In current political practice, countries condemn illegal aggression of one state against another state, except, when they feel threatened, they do just that. President George W. Bush, for example, invaded Iraq and President Nixon authorised a bombing campaign against Vietnam – even though the ‘threat’ to the United States was remote. At the present time, Turkey has invaded Syria. None of these illegal actions can be held, morally, to condone other illegal actions, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine. They do, however, constitute widely accepted norms of political action which states often claim are legitimate when they defend ‘higher level’ Western civilisational values, or state security. Western democracies, for example, in the Second World War, destroyed civilian populations by bombing and devastating Dresden and Hamburg and, more recently, Iraq.

The idea that the United States or Russia would be justified in attacking a neighboring country because they aligned militarily, or even economically, with another powerful country comes from the “sphere of influence” concept in international relations. In this concept, powerful countries have an interest in dominating the smaller countries around them. This control can be achieved through various means, such as economic, political, military, or cultural influence. The dominant power may assert its authority to protect its own interests, ensure regional stability, or prevent the influence of rival powers.

The sphere of influence notion has been significant in Russian foreign policy for a long time, particularly in its relations with neighboring countries and former Soviet republics. Russia has historically viewed these regions as falling within its sphere of influence due to cultural, historical, and geopolitical factors.

Despite the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia has sought to maintain influence over the former Soviet bloc countries, considering them as part of its strategic and security sphere. Thus, Russia has employed various means to assert its influence in the region, including economic ties, energy resources, political pressure, and military interventions. For example, the 2008 conflict with Georgia and the annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014 are examples of Russian actions to protect its perceived sphere of influence.

While this kind of behavior has been a regular occurrence by powerful countries, I hesitate to agree that it’s a “norm.” Regardless of whether the United States or Russia is the major player—you can’t logically have it both ways. The rule of law and the spheres of influence approach are contradictory. Either a country has a sovereign boundary respected by everyone or they don’t.

In fact, NATO opposes the spheres of influence concept. The organization is founded on principles of collective defense, cooperation, and the promotion of democratic values. NATO's perspective is rooted in the belief that all nations have the right to determine their own political systems, make sovereign decisions, and pursue their own security interests without interference or coercion from external powers.

Wouldn’t it be unfair to say just because a country like Estonia is small that they are forced into one economic or military bloc or another? This is a recipe for war in itself as either the major country then has latitude to dominate the countries in its sphere, or major countries go to war over some middle country. Thus NATO has allowed anyone to join based on their open-door policy. This is not a takeover of other countries and assembling a huge military force, it is allowing other countries to join—and leave—if they choose.

So as David Lane also notes,

Each European country had the right to choose its own security policy – to join any political or military alliance. These rights were defined in the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 to which the USSR had subscribed. The reasoning here is that a state cannot be truly ‘independent’ if it lacks the power to join the alliances it believes will further its own security interests. This forms the basis of the Ukrainian government’s politically legitimate right to join NATO, a right moreover which is implied in the USSR’s recognition of the Helsinki Agreement.

Applying this discussion to the United States and a hypothetical Chinese base in Mexico, we can conclude three things: First, the United States would likely use every possible approach first without attacking. There would be diplomatic talks, complaints, repositioning of other military assets, and so forth. Second, maybe the United States would attack. Third, it still wouldn’t be legally justifiable.

Invading is illegal. Provoking is not.

The Proof Is in the Results

Putin knew full well that NATO was not going to attack Russia. He certainly knew what the troop concentrations were, and he has 2,000 tactical nuclear weapons. Russia has the largest nuclear weapons arsenal in the world, and for that reason alone it cannot be invaded or taken over by military means.

More likely, the threat was really political and economic. Putin wanted to retain his sphere of influence and was losing a big chunk of it as Ukraine turned westward. Joining NATO would effectively end his ability to dominate them as part of his sphere of influence.

You don’t attack a stronger opponent that you think is going to retaliate and crush you. If you are using military force, you attack weaker opponents, and it might have seemed that the U.S. and NATO were getting weaker and not paying attention.

He probably had some seemingly strong signs:

The U.S. reaction to the annexation of Crimea and other Russian military adventures was tepid.

Former President Trump many times talked about having the U.S. withdraw from NATO.

Many Western countries took on big debt during COVID.

The massive protesting of the Black Lives Matter movement and the attempted coup during the Jan 6 Capital Riot might have led him to think the U.S. was very divided and too busy with its own problems to respond to his invasion of Ukraine.

So, Putin figured he could take his shot and was probably shocked that NATO and the West responded the way they did. Instead of ignoring Russian aggression, NATO cohered and became stronger. Rather than preventing Ukraine from joining NATO, Russian actions have accelerated it. Even more, the invasion of Ukraine has encouraged other—formerly neutral—nations to seek NATO membership as now Finland and Sweden have joined.

This map by Patrickneil shows the current situation well:

The net conclusion? From The Economist,

It is also a rebuke to those who argue that NATO shares in the blame for the war. Mr Putin is not alone in arguing that the alliance’s expansion into central and eastern Europe after the cold war somehow made Russia’s position intolerable. Plenty of Western scholars concur. However, the choice of Finland and Sweden suggests that they have the argument upside down. Countries seek to join NATO because they are threatened by Russia, not to antagonise it.

Why did NATO unite, then, was it because of President Biden's influence?